Maxwell Alexander Gallery artist Teal Blake is featured on the cover of October's issue of Western Art Collector Magazine. Pick up a copy today, and see more of Teal Blake's artwork HERE

Maxwell Alexander Gallery Artists Honored at Eiteljorg Museum's Quest for the West Art Show and Sale

Eiteljorg Museum's Quest for the West Art Show and Sale featured several Maxwell Alexander Gallery artists. Artist Glenn Dean was awarded with the prestigious Victor Higgins Work of Distinction Award for best body of work, and Josh Elliot with the Harrison Eiteljorg Purchase Award.

Harrison Eiteljorg Purchase Award

Josh Elliot, "Calving Season," 2016

Oil, 24" x 58" .

Work by Glenn Dean at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana

Southwest Art Previews “Looking Forward” May 2016

Culver City, CA

Maxwell Alexander Gallery, May 14-June 11

This story was featured in the May 2016 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art May 2016 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

G. Russell Case, Glenn Dean, Billy Schenck, and Tim Solliday—these are not your grandfather’s cowboy painters. Maxwell Alexander Gallery has gathered together the four artists to showcase what it perceives to be a shift in western art, one which hews faithfully to the genre’s much-beloved subjects—wide vistas, lone men on horseback, and mythically stoic Indians—but often with more graphic sensibilities that reimagine the classic themes. The show, entitled Looking Forward, opens on Saturday, May 14, with a reception from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. The gallery’s location in a now-hip area of Culver City is, fittingly, steps away from a few of the former movie studios where some of film’s best-loved westerns were produced.

“All of these guys are taking elements from the past and pushing the genre forward,” says gallery owner Beau Alexander. “Their subjects are characteristically western, but the group’s approach is fresh and exciting.” While each artist’s style differs from the others, Alexander sees their shared focus on design and a particularly contemporary way of “putting paint down on a canvas” as a compelling reason why young collectors are so drawn to their work.

“We all have a love of outdoor light,” notes widely collected painter Tim Solliday. “And we resist a photographic look. Our paintings may not be entirely literal, but they are true and full of life.” HUNTER’S MOON, one of the two or three pieces the artist is contributing to the show, captures the waning light as an Indian paddles home, his canoe heavy with the weight of a just-killed deer. Undeniably contemporary though the work may be, it nonetheless demonstrates the direct inspiration of early 20th-century American illustrators.

In similar spirit, paintings by Glenn Dean are at once contemporary—reducing shapes to their most essential parts—and nostalgic, informed by the rich history of other painters who gravitated toward the West. Populating his landscapes with figures is still a relatively new element in Dean’s work.

On the surface, works by G. Russell Case and Billy Schenck appear to be dissimilar. Case’s painterly style contrasts starkly with Schenck’s pop-art stylizing. Both artists’ pieces are confident and rife with subjects specific to the West, yet their canvases seem nearly to be wrought from different materials. Still, like every artist in Looking Forward, what connects them is a paring down to the most elemental. Indeed, as Alexander notes, “These artists are making brave choices and breaking away from tradition. It is a different time for western art”—a time steeped in history, certainly, but thrumming with a new vitality. —Lynn Dubinsky

– See more at: http://www.southwestart.com/events/maxwell-alexander-may2016-2#sthash.SVUsTmQG.dpuf

Western Art Collector Previews “Looking Forward” May 2016

Opening May 14, Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Culver City, California, will host the exhibition Looking Forward featuring around a dozen works by artists Glenn Dean, G. Russell Case, Tim Solliday, and Billy Schenck. “This group, among a handful of other artists in American art, are really pushing the contemporary aspects and leading Western art into a new direction,” says Beau Alexander, director of the gallery. “Maxwell Alexander Gallery is extremely focused on looking forward and putting shows together with artists whose work is the new breed of fine art.”

While on a trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico, Case came across his inspiration, and gathered references, for the painting Riders at Long Mesa. “Driving the road from Flagstaff [Arizona] to Santa Fe, one crosses some wonderful desert mesa country. The skies were loaded with clouds and the light, being late afternoon, was perfect for atmosphere and contrast,” Case describes. “This condition is among my favorite subjects, containing sharp display of the complements, blue of the sky with the terra- cotta mesas and ground.”

In a contrast, Schenck’s painting Big Sky Country has a lack of the landscape’s floor and focuses prominently on the horse and rider positioned against a billowing Western sky. The piece came about when Schenck saw a newspaper photograph of a horse with rider leaping up into an exaggerated position—a sight Schenck, who has a background as a rider, says he’s never seen before.

“I used to do rodeo paintings with the specific rodeo arenas with the crows nest in the background, but I haven’t done that since the late ’80s, early ’90s,” Schenck says. “Now, setting a figure like that in motion in midair makes it more dramatic and more surreal, with no reference to ground or anything at all other than the sky.”

Solliday’s work Hunter’s Moon developed into its final composition as the artist painted. Beginning the work, Solliday knew he wanted to paint a Northern-based scene of an Indian warrior heading back to camp after a hunt as viewed through beech trees. “I started to do it just like that, in a midday setting. Then, I started messing around with the composition and liked the moon behind his head…It had a real spiritual kind of feeling with the moon rising up behind him at that hour,” Solliday says. “I did a small study…and roughed it out. To see those darker colors with that high-key moon is what really made me want to do the picture.”

Another work focusing on twilight, or dusk, in the show is Dean’s Sunset Trail. The piece depicts two riders, one sitting atop his horse and the other leading him by his reins, as they walk through the wide-open, and seemingly never-ending, desert as the sun begins to set.

Looking Forward will be on view at Maxwell Alexander Gallery through June 11.

Fine Art Connoisseur Interviews Logan Maxwell Hagege regarding “THE WEST”

A Californian Looks Southwest

Maxwell Alexander Gallery will host its first solo show by Logan Maxwell Hagege (b. 1980), who has won acclaim for his luminous oil paintings of Southwestern people and scenery. That subject matter could not have been anticipated when this lifelong Angeleno graduated from high school and began a two year, full-time course of study at Associates in Art in nearby Sherman Oaks. There he mastered both life drawing and landscape sketching, complementing his studies with private instruction from the figurative artist Steve Huston and the landscapist Joseph Mendez.

Hagege’s earliest paintings were sparkling, pastel-hued scenes of beaches and city streets, somewhat in the spirit of Joaquin Sorolla. That changed when the young man traveled with other California painters, including Calvin Liang, Mian Situ, and Charles Muench, on a plein air road trip to Arizona’s arid, and starkly beautiful, Canyon de Chelly. “The landscape felt geometric to me,” Hagege recalls, so he began using deftly drawn graphic shapes, Southwestern colors, and strong lights and shadows to depict high-desert mesas and red-rock formations, the resourceful Hopi and Navajo people, and the animals who inhibit this terrain as well as the scudding clouds for which the region is renowned. (He depicts cowboys, too.) This signature style reminds us of the simplified forms perfected by another Californian, Maynard Dixon (1875-1946), and also of later paintings by members of the Taos Society of Artists, like E. Martin Hennings (1886-1956). Even so, there is something about Hagege’s approach that reads as “now” rather than “then.”

Today, when he isn’t exploring the Southwest, Hagege can be found working in his spacious studio in a warehouse int he San Fernando Valley. We look forward to learning where his vision will transport us next.

Western Art Collector Previews “THE WEST” by Logan Maxwell Hagege

In his first solo exhibition in his home state, Logan Maxwell Hagege returns to the desert landscape that captivates his work.

By Michael Clawson

Acruelty hides in the desert’s vast expanse: the scorching sun’s unblinking eye, the poisonous creatures lurking in yawning lairs made of broken rocks and loose soil, the endless plains of sand and sage, and the retreating moisture of the desert floor rippling upward in defeat.

We look out upon the desert to admire its beauty, but in the back of our thoughts we are afraid of this place and its ability to make us feel so small in the universe. The figures within Logan Maxwell Hagege’s works gaze upon this place with a calm majesty, but their faces are reserved, frozen in silent contemplation as the sun caresses their gentle expressions of worry, doubt, fear, hope, awe, wonder—their faces are blank slates to whatever emotion the viewer finds most fitting.

Hagege remembers a time when he was younger, when he would stare out the window and marvel at how the landscape bounced and stretched from the highway as the car followed the path and contour of the road. At night he would look up at the stars and see them move. He was fearless then—and many say still fearless today—and the desert was, as terrifyingly bleak as it was and still is, a magical place, a setting where the heat and the danger were footnotes to the inherent beauty of a fantasy with green orbs of sage sprouting from the dirt, sunsets in orange and pink and green, and domes of clouds that towered to the heavens.

The California artist’s depiction of the desert and its many facets will be on view in The West, opening April 9 at Maxwell Alexander Gallery. The show, Hagege’s first solo show in California, will feature his now-classic style of painting: realistic human figures within the desert, painted in a graphic quality with bold composition, a rhythm of shadows that alternate light-dark-light-dark to accentuate form, and vividly colored scenery rendered in a flat simplicity that brings out the detail and shape of his figures. Think Edgar Payne or Maynard Dixon done with a contemporary edge.

“The landscape is what originally brought me to the West. That’s where I started out and where I stayed until I learned what I wanted to say about the desert. Some of it was just experimenting,” Hagege says, adding that his interests changed as he spent more time in his locations. “I started meeting people, and then I met more people, and I started to find my voice. Suddenly it started going deeper and deeper—first Navajo blankets and weavings, then Pendleton camp blankets, Hopi kachina dolls…a whole new world was opening up for me. Each time I discovered something it was opening up new subcategories for new discoveries.”

Hagege and his unique works have been unequivocal hits in Western art, even among the burgeoning field of contemporary artists— Glenn Dean, Mark Maggiori, Jeremy Lipking, Josh Elliott, all friends of Hagege—who are striking new paths that some of the older generations had never attempted. Not only is he in important collections from coast to coast, he has works in important museum collections, he has appeared at some of the most prestigious art shows in the country, and he has won top honors at those shows, most recently at the Masters of the American West exhibition at the Autry National Center, where he shared the winner’s circle with George Carlson, Howard Terpning, and Len Chmiel, to name a few. Any way you count it, Hagege has had a streak of recognition that doesn’t seem to be ending any time soon—on top of it all, he and his wife are expecting their first child. And although he has found great success with his figures in the late afternoon desert, he’s always leaving his options open for new discoveries to creep in.

“I never sought out to be a Western artist. When people ask what I do I don’t say I’m a Western artist. I say I paint the American landscape and Native American figures. I don’t put that label on myself simply because I want to be free to paint what I want. But the West certainly inspires me,” he says. “I’m honored that my works are collected the way they are, and that I can sell a painting in New York City as easy as I can sell a piece in Santa Fe. It’s a great place to be.”

Works in the new show once again tackle Hagege’s complex narrative of the West: the desert as a place of terrifying silence and also limitless beauty, Native American figures wearing an assortment of weavings that absorb and reflect the light of the sky and desert, and landscapes with a variety of Hagege hallmarks, including his clusters of pillowy clouds and bouquets of abstracted sage painted into the desert floor. The sage makes a prominent appearance in Far Behind, where it crowds at the feet of a horse carrying a female figure, her eyes peering into our souls from behind the paint. In The Clouds Are Moving, he paints one of his favorite subjects, Apache model Chesley Wilson, as he stands in profile against dramatically lit clouds that emerge from the horizon.

In an untitled 80-by-80-inch piece that is still unfinished, Hagege paints a number of figures as they stand facing the sun, meeting its warm rays on their own terms. It’s one of his more elaborate pieces, with many elements balanced within his cloudy desert scene.

“Everything in my paintings, every element, is used as a compositional tool to move the eye around the canvas in a certain way. It’s an intuitive thing I create when I’m painting; it’s not always obvious at first. For The Clouds Are Moving, I frame the dark side of a face against the light side of a cloud to create that repetitive element that brings out the shapes even more. Sometimes I’ll use a halo effect or mimic the shape of the figure in the shape of the clouds,” he says. “As I’m drawing and planning my composition I’ll analyze the painting and start planning some of this out. Some of it is unintentional, and others are there because I saw them and designed them into the painting. It’s like cooking: you can taste the food while it cooks and make adjustments as needed.”

Ultimately, he says, “It’s about me pushing things to see how far I can take them.”

Landscape painter Josh Elliott says he admires Hagege’s works because they speak for the artist on his behalf. “What I find so compelling about Logan’s work is his keen sense of observation and conveyance of truth with his own voice. Look at how he searches out and accurately portrays reflected light, or carefully depicts subtle gradations in his skies and shadows. He reveals these truths in a stylized manner—he is telling us how he wants us to see them. In turn, through his exaggeration or accentuation, we can see the world through his eyes,” Elliott says. “One time I was driving with my daughters in the car, and one of them said, ‘Look, it’s a Logan cloud!’” Elliot adds that his designs are complex and reveal his deep attention to the craft of painting: “Logan has a strong sense of design, his compositions are well thought out but appear to be effortless. They are iconic and command attention. They are of the best kind—deceptively simple. He guides your eye through one of his paintings, but you’re not aware it is being guided.”

But guided it is. In the square piece This Mountain of Mine, round clouds and a deep-purple mountain ridge swing your eye around the top of the painting and down onto a brown horse, the slight curve of its tail sending your gaze further down and to the left, where it climbs up the horse’s front legs, through a cluster of vegetation, past the 45-degree angle of the horse’s head and back into the clouds. It’s a square painting, but it has a circular movement that revolves around the blanket-clad figure, who, like us, is trapped in the endless possibilities of Hagege’s West.

Southwest Art previews “THE WEST” by Logan Maxwell Hagege

Culver City, CA

Maxwell Alexander Gallery, April 9-May 7

This story was featured in the April 2016 issue of Southwest Art magazine. Get the Southwest Art April 2016 print issue or digital download now–then subscribe to Southwest Art and never miss another story.

Logan Maxwell Hagege says that his solo show, which opens on April 9 at Maxwell Alexander Gallery, is a homecoming of sorts: Titled The West, it’s Hagege’s first official solo show in Los Angeles County. “I grew up here, but I have always sent my paintings to other locations around the country,” he says. “Many friends, family, and collectors who rarely see my work locally will be able to see a cohesive group of paintings in one place, just a short drive from where many of them live.”

At 36, Hagege has already received much recognition for his boldly colorful, minimalist portrayals of cowboys and Native American figures—paintings that offer a unique contemporary vision of traditional western subject matter. His graphic, modernist works are held in prestigious museum collections at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles and the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. So in-demand are his paintings that most of the six to eight pieces in the current show are being sold in a drawing. “This is an opportunity we have today to experience a living master’s artwork fresh off the easel,” says Beau Alexander, gallery owner and director. “The artist’s ability to put together a complicated composition with perfect lighting and value, yet stripped down to the bare minimum, is second to none.”

Hagege first became intrigued with the West when, as a youngster, his family drove across the desert to visit his grandmother. The terrain of the region continues to intrigue him, and today it inhabits many of his works. But his passion also extends to the people and cultures of the West and Southwest and includes everything from the ceremonial objects associated with Native Americans to the accouterments of cowboy life.

Explaining the meaning of his art in great detail is not something Hagege favors; he believes that when viewers are told what to think and feel, it can ruin their experience of interacting with the art. However, he does offer a glimpse into his creative process when he speaks about THIS MOUNTAIN OF MINE, which is on view in the show. For several months, Hagege says, the image for the painting percolated in his mind. “I usually have several ideas floating around in my head, and I will paint a piece when the idea is screaming at me. This was the case with this piece,” he says. “I wanted to paint the stark white against the deep dark blue of the mountain. It is a light effect that I have seen before out in the desert. The landscape was painted from a memory of that light.”

Alexander is excited about the show because, as he points out, paintings of western subject matter are usually “typecast” and shown only in smaller cities such as Scottsdale, Jackson, or Santa Fe. But Los Angeles represents a major art market. “You can’t get any more main stage than L.A.,” he says, “and we are excited to have a group of paintings by Hagege available to some of the major art collectors in the world.” —Bonnie Gangelhoff

– See more at: http://www.southwestart.com/events/maxwell-alexander-may2016#sthash.jwtTRn1T.dpuf

American Art Collector Covers the Two-Man show Ft. Mann & Todorovitch

As artists, Jeremy Mann and Joseph Todorovitch figurative artist Todorovitch has been challenging are constantly finding new ways to challenge their himself by working more intuitively. “I’m trying to artistic processes; to push their paint application and mark making to new limits, allowing for exploration in each composition. This goes beyond the subjects they paint and speaks directly to their techniques.

Mann, who paints both figures and cityscapes, says, “If I don’t push myself further in my paintings, I’ll sink in the mud, both a physical challenge and also a mental hurdle. The best medicine to encourage this growth is travel and experience, with a healthy dose of long, thoughtful showers and bravery. To have the guts to try new techniques, approaches, watch new strange films, research photographers, draw from life, try different old cameras and lighting situations, new palettes of colors…a plethora of ways to add more garbage to the compost pile and grow something different.”

Echoing the idea of growth in his paintings, explore more with the paint application and at the same time balance a very strong sense of control, which is counterintuitive,” he says. “I really do crave control, but at the same time, I want it interesting and to be more willing to explore paint application and step outside my comfort zone—sometimes step outside a lot depending on what the painting allows.”

March 12 to April 2, the artists will exhibit in a two- man show at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Culver City, California. On display will be brand-new works that highlight their signature subjects as well as show artistic evolutions.

Included among the pieces by Mann is the cityscape NYC #20, which features a harmonious color palette— something that appears in many of his paintings. Mann explains, “Color palette should always be harmonized, it references the light and color when the city is bathed

in the atmosphere of twilight, artificial light or daylight. I believe that a control of an artist’s color palette is one of the most difficult things to handle, but also one of the most exciting when you’re on point. Having conditioned my approach, my monitors, my film references and my palette to reflect this desire, I leave finesse for my brain to conduct with when painting in the studio.”

One of Todorovitch’s paintings in the show is Comet, depicting a woman in a red dress standing in a clothing store. “I was working with the model, and based on what she had brought to work with in terms of wardrobe, I thought it’d be really fun to counter that with something that was more textural—a background that has a lot of activity, and was very active against the simple red dress,”

says Todorovitch. He adds that when working with models, “I like to just get the model in the environment and start moving around—play with color, shapes, value and simple picture-making ideas until it starts to feel right. I’m trying to work intuitively more and more, and not overthink the process…” and viewers will see juxtapositions such as a “highly rendered face next to something abstract.”

Todorovitch also has noticed a common thread of perception in his new works. “Obviously I’m concerned about the visual experience we construct from nature about our reality with all the wonderful and clever ways we use paint to represent that. But also, perhaps more subconsciously, the perception of the subject and viewer experience,” Todorovitch says. “How the subject perceives being viewed and how we view the subject has naturally become a part of the process working with friends, family and strangers. I wouldn’t object to the use of particular staging and objects adding a deeper layer of psychology to the paintings so long as it isn’t focused… This also presents opportunities to demonstrate intricate painting skill. All very important to me.”

Western Art Collector Previews the Monument Valley group show

Each year for the past three years, Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Culver City, California, has hosted a group landscape show based on a specific location to garner various interpretations of a breathtaking locale. Gallery director and owner Beau Alexander calls the destinations “magical,” and says this year’s Monument Valley focus is “about as unique as you can get from any other landscape in the rest of the world.”

“With a group landscape show like this, we really get to seen an artist’s perspective,”

says Alexander. “If this were strictly a figurative show, each artist would paint a figure they like in their style. We’d be able to see different viewpoints, but ultimately, the subject would be different, and it would be hard to see differences. A landscape like Monument Valley isn’t going to change, and most of us all see it the same, but by asking artists to all paint this iconic location, we really get a chance to see what the artist sees. This exhibition will truly show the artist’s vision.”

The 10 participating artists include Logan Maxwell Hagege, Mark Maggiori, and Scott Burdick. The exhibition will feature about 15 works, ranging from the dramatic cloud-filled oil on linen Dark Clouds, Monument Valley, by G. Russell Case; to the exaggerated shapes found in Tracy Felix’s abstract-tinged oil on panel Valley Towers; to Billy Schenck’s oil on canvas Coming from the Bisti and Glenn Dean’s oil Navajo Moonrise, featuring Navajo figures on horseback.

David Grossmann, represented with his oil on linen panel work Stone and Cloud Patterns,

has been painting in Monument Valley for years and says the area brings out emotional feelings for him, of feeling fragile and temporary. “In Monument Valley, there is an immediate sense of contrast because the vastness of the landscape makes everything else feel insignificant,” says Grossmann. “That morning in Monument Valley that inspired this painting was a reminder to me of how grateful I am for my life as an artist and for these opportunities to find inspiration in such wonderful places.”

Western Art Collector Previews Mark Maggiori’s Debut Solo Exhibition

When Mark Maggiori was 15 years old, he flew from his home in France to New York for a month-long visit that would include a coast-to-coast drive through America’s vast natural and cultural landscape. From the steel and concrete of the big city, he traveled through the sprawling heartland and into the West, where towering rock formations beckoned his arrival. In On the Road, Jack Kerouac wrote, “I was halfway across America, at the dividing line between the East of my youth and the West of my future.” Maggiori, transfixed by the desert’s beauty, had reached his own dividing line.

“The American West had already imprinted on my brain at that point. As a boy I would play with a cowboy hat and pistol, watch Western movies and read about cowboys,” Maggiori says. “But when I finally came here, and saw Monument Valley and Canyon de Chelly, it started to connect for me in bigger ways. Those sights, those places—they all looked like big movie sets—they created very strong memories for me, and I suddenly understood the West and what it was.” After that initial visit and road trip west, Maggiori

returned to Europe to embark on his own path forward, one that was then, and still is today, wholly unique to Western art. He formed Pleymo, a French nu-metal band that traveled the world and released a handful of successful albums. He also began exploring other artistic avenues with photography, filmmaking and animation. In 2007, the band dissolved and Maggiori, like Henry Farny before him, left France and came to the United States. Here he pursued his photographic endeavors, from elaborate feature films to music videos for an array of musical groups to his intimate—at times, erotic—photography of figures eloping into the myth of Western culture.

To appreciate this era of Maggiori’s career, and to punctuate how unique his entry into Western art is, it’s helpful to remember some of the tenets of the American West: country music, conservative values, modest dress and attitudes, and national pride. And here was a Frenchman, a former singer in a metal band, coming to the Southwest to photograph nudes in provocative photos shoots and to create art that broadened the interpretation of the West. To say he was an outsider is an understatement, yet as soon as he started painting cowboys, and showing his unmistakable talent, he was accepted by the old guard and the new.

“I’m definitely different. I come from a completely different culture, and my background already set me apart from others. Sometimes I wish I hadn’t done those things and instead started painting earlier. But then I realize I’m happy of the other things I’ve done, because now I can use those things to inform my paintings,” Maggiori says from his Los Angeles studio. “It’s also very interesting to share these new moments with other artists. I went to the Cowboy Artists of America, with artists like Teal Blake, and they all do things very differently. They’re true cowboys. In many ways, those artists and I are completely opposite from each other. Yet, we see things in the same way, and all those differences disappear when we’re painting.”

Maggiori was so new to Western art when he started that he was still unfamiliar with many of the great artists, including Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell. “I’ve been discovering as I go. I was familiar with Norman Rockwell and John Singer Sargent in France, but they are very international artists,” he adds. “I only discovered the Taos artists two years ago. I didn’t know who Walter Ufer was, or even Frank Tenney Johnson. I still get on the Internet and look up new artists, and I’m learning more all the time.”

These are remarkable revelations from someone who has revealed such a deep appreciation of the West and a remarkable ability to capture it in new ways. Painter Logan Maxwell Hagege, who discovered the French artist and immediately began promoting his work within the Western art market, ties Maggiori’s quickly developing skill back to his love of the West. “He’s a breath of fresh air to this whole world, and you can see it in his work. It has an old world sort of feel to it. It links back to Remington, and the Taos artists. His works feel old, but they have a contemporary edge to them,” Hagege says, adding that he met Maggiori, an avid buyer and reseller of vintage clothes, through a hat maker friend. “He’s an interesting guy, and he’s done such a wide variety of different things, from bands in France to vintage clothing to videos…it all just strengthens him as an artist.

It also makes him stick out, but in a good way. He’s definitely an outsider, and his work has an outsider feel to it.”Maggiori’s solo exhibition, Alone in the Wild—opening October 10 at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Culver City, California— will be the world’s first full glimpse of this international enigma that has taken the West by storm. The title of the show is a reference to the artist’s days in Kingman, Arizona, where he was holed up by himself for several months before joining his wife, and frequent muse, who had taken a job in Los Angeles.

“During that time period, Mark was painting in seclusion. And similar to his paintings, which depict a lone cowboy on the range, he felt like he was in his paintings. Mentally and figuratively, he was alone in the wild,” says Beau Alexander, co-owner of Maxwell Alexander. “Having been born in France and growing up there as well, his vision is completely unique. His experience of the American West started as an outsider, but his many years living in small dusty desert towns have made him an authentic Westerner, both in his art and his spirit. Before his move to Los Angeles, he had the letters ‘A-R-I-Z-O-N-A’ tattooed on his forearm to pay homage to the West that has given him his muse. His dedication to the West is seen in his work ethic as well as his many trips into the lonely deserts to find his subjects.”

The works in the show are timeless depictions of horse and rider in a variety of landscapes, from dusty perches above canyon rims to low-lying flatlands dotted with desert sagebrush. In The Kaibab Trail, he paints a rider and two horses framed against the Grand Canyon, its majestic etching of the earth seen from a high angle and in tremendous detail. Many of his pieces are imbued with motion: riders hunched back as their horses descend a sandy slope, a horse mane bouncing upward during a steady gallop, a rope in an accordion- like freefall as a bronco bucks. He also paints sumptuous nocturnes that would make Frank Tenney Johnson proud—his blues sparkle, subtle shadows dance on the soil, and moonlit clouds balloon out over the desert floor.

Clouds also play a prominent role in Down the Wash, featuring a cowboy descending a dusty hill. The horizon line separates the warm earthy tones of the desert from the cool blues and whites of the sky. “I find that I’m mostly interested in the pose and the action. With that one it was the dynamic of the guy and the horse,” Maggiori says. “Lately I’ve found models for my paintings. Sometimes they lean forward or stay very straight. Typically I tell them to stay very straight, and then I change the cowboy figure in the painting. I like to change what I’m actually seeing, to see how I can make it better or more interesting. There is so much to learn, so I just try to see what works best for me.”

Maggiori says he’d like to start experimenting with historical works, a subject that has recently been fascinating him. “I’m very touched by the story of America,” he says. For now, though, he continues to have his hands in many projects, including new paintings. “This work is very hard, and sometimes I have to ask myself what the fuck I’m doing. It’s such a lonely road sometimes. When you’re in the studio, there are days it’s very uplifting, and then there are days where it’s a real struggle. Luckily, there is much out there to see and paint. The West is such a huge culture and an important American tradition.” It’s an American tradition that he is now contributing to. And in a big way.

Southwest Art Previews the Mark Maggiori Solo Exhibition

This story was featured in the October 2015 issue of Southwest Art magazine.

A cowboy leaning against a fence at the end of a long day could easily be an image from painter Mark Maggiori’s repertoire, but the scene also describes the artist himself. The Frenchman-turned-American has immersed himself in the culture that first captured his imagination as a teenager, donning the look by dressing in vintage cowboy wear and adopting the lifestyle by spending weeks on the range in Arizona and Utah. It’s all in service of creating the paintings in his first-ever solo show at Maxwell Alexander Gallery this month. The show opens with an artist’s reception on Saturday, October 10, from 7 to 9:30 p.m.

Maggiori first traveled the American West when he was 15; Monument Valley and Canyon de Chelly left an indelible impression on him, and he vowed to return. The multifaceted artist went on to graduate from the prestigious Academie Julian, in Paris, and then traveled the globe with a rock band, eventually migrating to Arizona with his wife. For the past two years he’s devoted himself to painting full time and has chosen cowboys, the iconic figures of the American West, as his exclusive subjects.

Artist Logan Maxwell Hagege first discovered Maggiori’s work, recommending him to Maxwell Alexander Gallery, which became the first to show the Frenchman’s work. The gallery has been instrumental in guiding his career during the lead-up to this solo debut.

“Over the past year and a half, he’s really developed his style and technique. He’s ready for it,” says gallery owner Beau Alexander. “Maggiori is bringing a breath of fresh air into western art.” Alexander cites Frank Tenney Johnson and Frederic Remington as two of the artist’s influences, yet observes that Maggiori’s work feels wholly contemporary. Drawing upon his background as an illustrator, photographer, and music-video director, he arrives at a unique vision that feels alive. He renders cowboys and horses realistically, while his loose brushwork pulls the backgrounds into impressionism.

“Cowboys are a very strong image of freedom. They represent a time when everything was possible here,” Maggiori says. His view of cowboys today, however, is grounded equally in romanticism and reality. Currently based in Los Angeles, the artist does studies on location and spends weeks with his favored subjects. “It’s amazing to see cowboys actually leading this life,” he adds.

The 15 or 16 pieces in the show took shape when Maggiori followed cowboys from dawn to dusk, capturing them in the varied conditions of their work. The resulting series depicts the cowboys during overcast mornings, in the bright light of high noon, and in the cool hues of night. Each portrays a cowboy feeling much as Maggiori did while painting the series—alone in the wild and dwarfed by the vast landscape. His pieces show a cowboy leading a pack horse down the Kaibab Trail at the Grand Canyon and riding in a wash with a storm rising in the distance, among other scenes. In these pieces, Maggiori says, “You don’t know when the rides started or when they are going to end.” —Ashley M. Biggers

– See more at: http://www.southwestart.com/events/maxwell-alexander-oct2015#sthash.H0MDR0kB.dpuf

American Art Collector Previews “Still” by Michael Klein

Michael Klein “Still” Exhibition:

In Elton John’s 1972 hit Mona Lisa’s and Mad Hatters the singer opens the song with this poetic serenade: “Now I know / Spanish Harlem are not just pretty words to say/I thought I knew/But now I know that rose trees never grow in New York City.” This was an artist pondering the beauty of the world, and its many limitations.

Painter Michael Klein has been exploring similar themes from his studio in, as luck would have it, Spanish Harlem, an arts- and culture-filled neighborhood on Manhattan’s northeastern shoulder.

“When you paint flowers, and when you step into the area of beauty, it’s so easy to fail. It can look too saccharin or sweet,” says Klein from his New York City studio. “It’s hard to take those subjects and make them beautiful on a deeper level.”

Klein, who has a new solo exhibition opening September 5 at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Culver City, California, says that early in his career he was taught by artists who were believers in the Boston School of painting, particularly R. H. Ives Gammell, but he quickly discovered limitations to the style within his own work. Klein eventually found Jacob Collins, an artist and teacher who was developing a different style of realism, one that appealed on a broader level to Klein’s interests with figurative and still life subjects.

“They were searching for beauty, and it was a profound beauty that spoke to and resonated with me,” Klein says. “They did two things that won me over right away: first, the color palette. You hear impressionists and other artists talk about never using black, but I wanted to use black because it was important to the tone of my work. Secondly, there was emphasis placed on drawing, which I loved, and Jacob is an extremely good draftsman.”

Klein says he paints from life, using live arrangements he sets up in his studio, but he can easily add to it based entirely on memory. In Studio Peonies, for example, he had originally painted the flowers closed, but after several months he revisited the work—“the peonies were long gone,” he says—to paint the flowers opened up, thus altering the very core of his delicate subjects.

“Painting from life is a huge factor for me. With color, I usually try to keep the colors relatively harmonious. I don’t want too much color, and I don’t want it to be overwhelming,” he says. “I want the painting to be about the poetry of the subject.”

Other works in the floral exhibition include Pot with Dried Rose and Pink English Roses, a painting with a composition and tonal qualities that Klein compares to a musical arrangement.

“There is always a shadow, always a neutral and always something really chromatic. As things get more into the light, they become more chromatic,” he says. “I don’t want the works to be bland or dull; I want there to be good color notes. It’s like bass and treble. Imagine a flute or something fluttering over the bass. But with all bass, it becomes too heavy. There has to be a balance there for everything to work.”

Western Art Collector Covers Glenn Dean’s Exhibition “The American West”

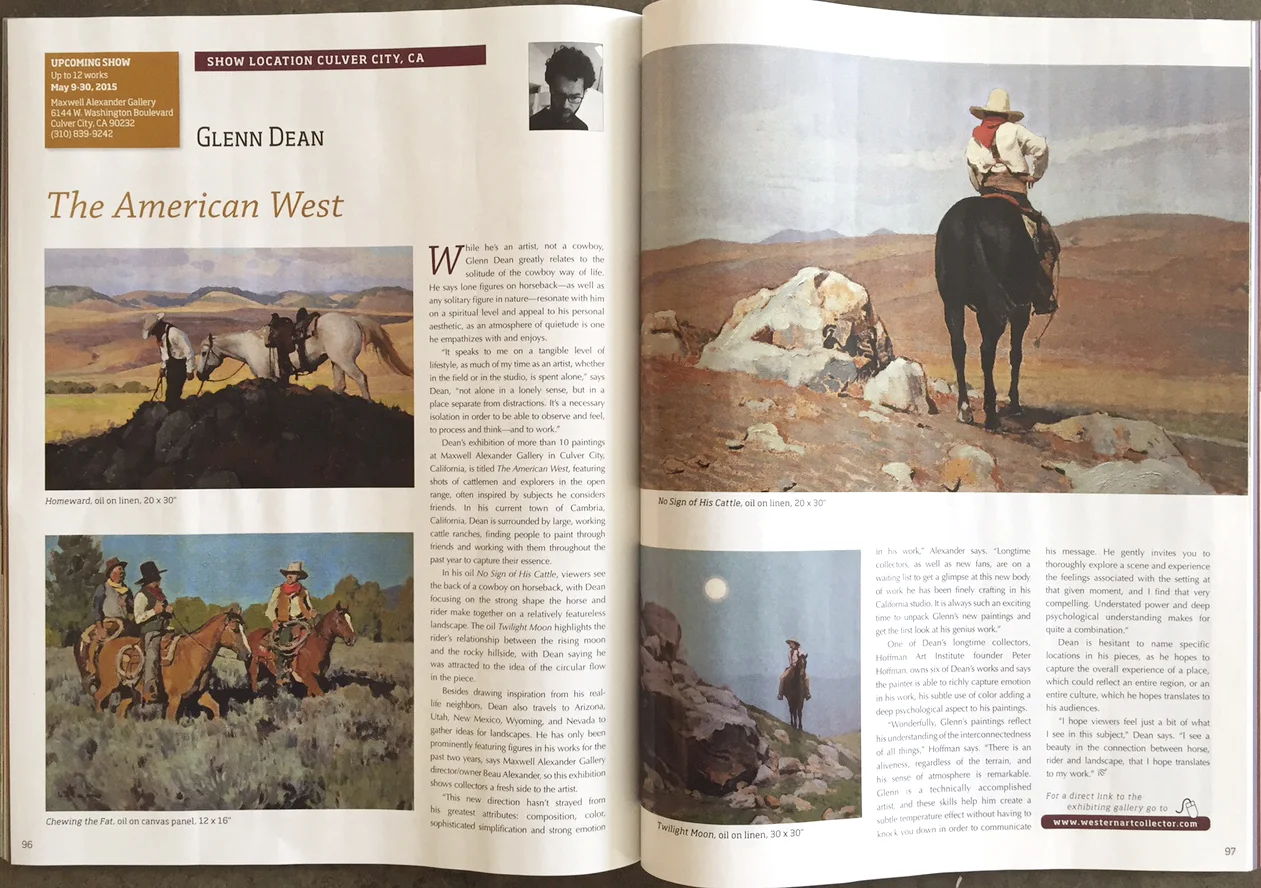

While he’s an artist, not a cowboy, Glenn Dean greatly relates to the solitude of the cowboy way of life. He says lone figures on horseback—as well as any solitary figure in nature—resonate with him on a spiritual level and appeal to his personal aesthetic, as an atmosphere of quietude is one he empathizes with and enjoys.

“It speaks to me on a tangible level of lifestyle, as much of my time as an artist, whether in the field or in the studio, is spent alone,” says Dean, “not alone in a lonely sense, but in a place separate from distractions. It’s a necessary isolation in order to be able to observe and feel, to process and think—and to work.”

Dean’s exhibition of more than 10 paintings at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Culver City, California, is titled The American West, featuring shots of cattlemen and explorers in the open range, often inspired by subjects he considers friends. In his current town of Cambria, California, Dean is surrounded by large, working cattle ranches, finding people to paint through friends and working with them throughout the past year to capture their essence.

In his oil No Sign of His Cattle, viewers see the back of a cowboy on horseback, with Dean focusing on the strong shape the horse and rider make together on a relatively featureless landscape. The oil Twilight Moon highlights the rider’s relationship between the rising moon and the rocky hillside, with Dean saying he was attracted to the idea of the circular flow in the piece.

Besides drawing inspiration from his real- life neighbors, Dean also travels to Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Nevada to gather ideas for landscapes. He has only been prominently featuring figures in his works for the past two years, says Maxwell Alexander Gallery director/owner Beau Alexander, so this exhibition shows collectors a fresh side to the artist.

“This new direction hasn’t strayed from his greatest attributes: composition, color, sophisticated simplification and strong emotion in his work,” Alexander says. “Longtime collectors, as well as new fans, are on a waiting list to get a glimpse at this new body of work he has been finely crafting in his California studio. It is always such an exciting time to unpack Glenn’s new paintings and get the first look at his genius work.”

One of Dean’s longtime collectors, Hoffman Art Institute founder Peter Hoffman, owns six of Dean’s works and says the painter is able to richly capture emotion in his work, his subtle use of color adding a deep psychological aspect to his paintings.

“Wonderfully, Glenn’s paintings reflect his understanding of the interconnectedness of all things,” Hoffman says. “There is an aliveness, regardless of the terrain, and his sense of atmosphere is remarkable. Glenn is a technically accomplished artist, and these skills help him create a subtle temperature effect without having to knock you down in order to communicate his message. He gently invites you to thoroughly explore a scene and experience the feelings associated with the setting at that given moment, and I find that very compelling. Understated power and deep psychological understanding makes for quite a combination.”

Dean is hesitant to name specific locations in his pieces, as he hopes to capture the overall experience of a place, which could reflect an entire region, or an entire culture, which he hopes translates to his audiences.

“I hope viewers feel just a bit of what I see in this subject,” Dean says. “I see a beauty in the connection between horse, rider and landscape, that I hope translates to my work.”

Southwest Art Covers Glenn Dean’s Exhibition “The American West”

Glenn Dean has proven himself to be a deliberate and adept painter of the American Southwest. Infused with his own brand of “simplified realism,” as he calls it, Dean’s canvases impart the inherent beauty he finds in his surroundings. He has always been interested in painting riders on horseback, and while these figures have appeared in his work from time to time as compositional elements, only recently has he made them the primary focus. Dean’s newest body of work, on display at Maxwell Alexander Gallery this month, gives viewers a more intimate look at these riders, as both integral facets of the environment and as storied protagonists.

Glenn Dean: The American West opens on Saturday, May 9, and continues through May 30. The gallery hosts an opening reception on Saturday, May 9, from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. The show includes a dozen new oil paintings, ranging in size from 12 to 40 inches across, and featuring riders and scenery from Dean’s native California and across the Southwest. Gallery owner Beau Alexander says, “Figurative works from renowned landscape painter Glenn Dean have been in development over the last several years. Dean has been studying and perfecting his figurative painting skills, waiting for the right time to share them with the public. It has only been about two years since he has started to feature figures in his western paintings more prominently. This new direction hasn’t strayed from his greatest attributes: composition, color, sophisticated simplification, and strong emotion in his work.”

Dean gathers material for his compositions in the field, observing, photographing, taking notes, and sketching. The resulting compositions feature shapes defined by color and wrapped in a delicate interplay of light and shadow. Figures and their settings display a slight abstraction while also retaining fundamental detail—evidence of the artist’s purposeful brushwork. He explains, “I try to paint my subjects in an honest and truthful way, while paying attention to artistic choices that might best reveal the more essential information of the subject.”

As he paints, Dean also channels history, finding inspiration in the rich aesthetics of late 19th- and early 20th-century western landscape painters. Like his predecessors, Dean has a great respect for nature and strives to mine both visual and spiritual elements within the landscape. “I want my work to speak of the things that I have found to be beautiful and powerful,” he says. “This can be in something simple, like a sagebrush, or something grand, like a towering desert monolith. Whatever the thing may be, I feel that it has a voice, its own separate breath of life, its own place in the world that fits just right … which, to me, speaks of the divine.”

Excited to show Dean’s figure-based collection for the first time, Alexander remarks, “Longtime collectors as well as new fans are on a waiting list to get a glimpse at this new body of work that Dean has been finely crafting in his California studio. It is always such an exciting time to unpack his new paintings and get the first look at his genius work.” —Elizabeth L. Delaney

– See more at: http://www.southwestart.com/events/show-preview-glenn-dean#sthash.Ay2AYKXq.dpuf

Western Art Collector Covers Tim Solliday’s Exhibition “The Native West”

When Tim Solliday is looking for inspiration, he turns not to other contemporary Western artists, but to the past, when artists were not only part of the public discussion but actually funded by the public through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ambitious plan to send Americans, including artists, back to work.

“My absolute favorite WPA mural is at the Los Angeles Public Library by Dean Cornwell, who was an American Illustrator. Those illustrators were like rock stars in the ’20s through the ’40,” Solliday says. “Cornwell, and the other illustrators, were taking fine art principles and using them in new ways. He wasn’t called an illustrator; he was called a muralist, which I just think is great. One of the things that appealed to me about those guys, especially Cornwell, was they were true to nature, but also more whimsical and fun. They put more life into their works.”

Elements of the great murals can be seen in Solliday’s new piece Migration, a 12-by-28-inch panoramic of a Native American migration. The painting, featuring 10 figures and numerous horses, was originally only intended to be a study for a larger piece that will be at the Prix de West in June. The owners of Maxwell Alexander gallery, where Solliday will be showing new works beginning April 4, convinced him to exhibit it at his show. Migration will be the centerpiece of new work by the California painter.

Other works include two nocturnes featuring looser brushstrokes–Home Fires, with a figure calmly standing in the moonlight, and Sacred Trees, with a horse and rider approaching a vertical wall of trunks and shadows– and the Pottery Painter, with a figure decorating vessels in a stand of trees. The pieces are done in Solliday’s distinctive illustrative-like style, with strong lines and thick edges around his subjects.

“The outlines are there to bring the figure closer to you, and it’s important for what I’m trying to bring out in the picture,” Solliday says, adding that sometimes he’ll pose figures just to create shapes within their poses, such as triangles that are created with the placement of arms against bodies. “I want to always emphasize the line, because design is very big for me. Logan Maxwell Hagege, for instance, is another guy who is really focusing on design. He knows how to lay out a painting.”

Solliday, who recently moved his studio into a room in an old church–“If the stained glass weren’t so faded it would create problems with the lighting”–says he wants to take what he knows about illustration, design and the idea of “the line” and apply it to scenes from the Old West.

“My big ambition is simple: I want to paint big figures and dramatic scenes,” he says, “and that’s pretty much it.”

Southwest Art Covers Tim Solliday’s Exhibition “The Native West”

Tim Solliday has always relished painting panoramic scenes. This month viewers have the opportunity to see one such signature Solliday work, MIGRATION, a multifigure painting that depicts American Indians moving across a western landscape on horseback. MIGRATION is one of about eight new works by the artist featured in Native West, a solo show that opens at Maxwell Alexander Gallery with a reception on Saturday, April 4, from 6 to 8 p.m. “Panoramic, progressive paintings offer me a great chance to show many different characters in expressive actions,” Solliday says. “Long, progressive paintings are very dramatic and make a great composition.”

The Southern California-based Solliday is an established artist and a regular participant in prestigious shows, including the annual Prix de West at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, OK. An early influence on his fine-art career, Solliday says, was studying with California Impressionist Theodore N. Lukits [1897-1992]. Solliday’s style and subject matter, though, is strongly reminiscent of Taos Society of Artists members such as Ernest Blumenschein and Ernest Martin Hennings. Like some of the Taos artists, Solliday is known for his expressionistic approach and vibrant colors in depictions of the southwestern landscape and its peoples. While the artist enjoys working on panoramic scenes, he also displays a penchant for nocturnes like HOME FIRES, a painting in the show that portrays an Indian chief standing by a stream while looking back at his village bathed in the moonlight.

Gallery owner Beau Alexander doesn’t hesitate to call Solliday a “living master. His numerous years of outdoor study and painting directly from nature give his studio pieces life beyond realism,” Alexander says. “Each piece is built up from preparatory composition sketches, then studies from life, and then onto the final canvas where all of the elements are combined. His traditional method of working is a throwback to an academic era in art, and his unique style is what makes him one of the most sought-after contemporary western artists today. If Solliday were alive in early 1900s New Mexico, he’d be welcomed with open arms as a member of the Taos Society of Artists.”

– See more at: http://www.southwestart.com/events/maxwell-alexander-apr2015#sthash.ieVk1FKX.dpuf

American Art Collector Magazine covers “Offerings” by Todorovitch

When California painter Joseph Todorovitch first started drawing and painting, he was creating multiple figures in elaborate scenes. Worried he was biting off more than he could chew, he dialed back to single figures, a choice he now realizes was very wise.

“My multiple figure pieces were more illustrative and conceptual. I slowly recognized the difficulty of what I was doing, so I started to only paint single figures…so that I could do them convincingly with all the wonder of nature,” he says. “I’m bringing those more complex arrangements back now that I understand the fundamentals better. I’m also really challenging myself with the mechanics, including dynamic pieces that have more anatomical nuance.”

The Pomona, California, artist and teacher specifically calls out to some of his work with ballerinas and dancers, including Mariposa and Swan, pieces that are examples of an idea Todorovitch refers to as the “gesture of the pose.”

“I’ve always been very sensitive to the spirit of the pose. I want my paintings to capture that eloquently, whether or not it’s an active pose or a passive pose,” he says. “There’s an undercurrent of beautiful and graceful gestures that can be found in humanity. That is what I’m painting.”

He is especially drawn to eyes, which unlock a whole new world of narrative and ideas, even before the piece is finished. “Eyes are universal. As soon as there is a pair of eyes in a painting, we connect as humans. There’s so many opportunities to present a story there. To look into the subject’s eyes is to see so much,” he explains. “We’re always trying to abstract our surroundings, even looking at people and presuming to know what they’re thinking. To convey psychology with paint is very special to me. I want to get in close and interpret that.”

In Lateef, Todorovitch paints a friend, his arms raised to his head and his face largely in profile. In Refresh, his model exists in

a world that seems mostly incomplete, her head fixed into an abstract space that accentuates her features and turned glance. These figures offer a silent mystery, which is an aspect Todorovitch tries to paint in most of his works.

His new solo show at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Culver City, California, is titled Offerings, and it leads right into these mysteries.

“It’s me reaching out and showing you how all this comes together. It’s an offering of my view,” he says, adding that viewers are encouraged to have their own view, as well. “I want to leave a lot of myself out of it. Other than my hands creating the paintings, there is no common theme except the one the viewer chooses. I hope the viewer sees something there for themselves.”

Southwest Art Magazine Covers “Trading Post” Curated by Logan Maxwell Hagege Dec 2014

Maxwell Alexander Gallery conjures the spirit of the Old West this month by transforming itself into a full-fledged early American trading post. The show, curated by gallery artist Logan Maxwell Hagege, pays homage to these iconic commercial and social destinations, celebrating them as integral to the proliferation of American art and to the advancement of a burgeoning multicultural society. Spurred by Hagege’s personal interest in the history of trading posts, the exhibition-installation creates a microenvironment that mingles contemporary fine art and craft with western and Native American memorabilia. Among the more notable showpieces in what Hagege calls a “hodgepodge” of collectibles is a pair of 1950s-era, 6-foot-tall kachina dolls, as well as a variety of Navajo rugs and jewelry. A selection of vintage and contemporary weavings and kachinas are for sale.

Trading Post opens on Saturday, December 6, with a reception from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. A broad array of offerings by 11 artists and artisans is for sale, ranging in price from $20 to several thousand dollars and appealing to a wide aesthetic. Gallery owner Beau Alexander says, “For me, the most exciting thing about going to trading posts is looking for treasure. Here, people will find unique treasures that a typical gallery wouldn’t be able to show.” Hagege adds that the show features his “dream list of superstar western artists.”

Gallery artists and special guests each bring two to three pieces to the show, including highly renowned western painters G. Russell Case, Glenn Dean, Jeremy Lipking, Mark Maggiori, and Tim Solliday. Award-winning painter Billy Schenck participates as well, contributing two paintings of late-19th-century kachina dolls. Reminiscent of subject matter that would have been available at a trading post, the paintings are done in the artist’s signature style, which contemporizes traditional themes and compositions. Graphically charged with vibrant, flat color and nearly indistinguishable brush strokes, Schenck’s paintings reference the photographs, posters, and movie stills prevalent in popular culture. Reflecting on the exhibition, Schenck remarks, “A lot of artists I consider peers, and that I collect, are in the show. I’m glad to be part of that. It’s like the Super Bowl for western artists.”

“The idea behind this show was to try and imagine what artists who are around today may have had for sale in the trading posts of the past,” Hagege explains. “This show will feature a mix of contemporary as well as vintage items that will give the L.A. crowd a feel for what a trading-post experience is like.” In addition to curating the show, he contributes two portraits of present-day Native American figures against stylized, light-infused backgrounds, linking traditional subject matter with modernist aesthetics.

Along with paintings, Trading Post offers a number of Old West and Native American pieces by award-winning kachina carver Randy Brokeshoulder; noted Navajo weaver Melissa Cody; Slowpoke leather goods; and artist Ishi Glinksy, who brings baskets made of baling wire that are inspired by traditional Tohono O’odham tribal forms. —Elizabeth L. Delaney

Western Art Collector Covers “Trading Post” Curated by Logan Maxwell Hagege Dec 2014

Western Art Collector Covers Mark Maggiori & Brett James Smith Two-Man Show Oct 2014

Maxwell Alexander Gallery brings together two exceptional artists for its October exhibition. Titled “Cowboys & Indians,” the two-man show features new cowboy works by Mark Maggiori and Native American themed paintings by Brett James Smith.

While well-known for his classic sporting scenes, Smith says his art has been evolving. About 20 years ago on a back country fly-fishing trip to Montana and Idaho he discovered a new and historically interesting subject to explore with his paintings: the West.

“At first my interest was in depicting my usual cast of sportsmen characters in this new environment,” explains Smith. “The creative possibilities seem inexhaustible.”

As he moved throughout the progression of his career, the need for a diversion from his usual repertoire of subjects became overwhelming.

As he remembers, “I was burnt out of the formula paintings. Although lucrative, I needed a creative place to go where there were no rules in designing pictures.”

Smith continues, “I feel it is unimportant in my designs to be affiliated with any particular group. Among the multitude of tribes of native people in North America, the customs, beliefs and religions varied from tribe to tribe. They differed as much as they were the same…their art and designs were unique only to individual. Inspiration was born from the mystic haze of dreams and these dreams would turn to nightmares as their fate played out. From the destruction of their culture rose the development and ownership of their land, a concept that was unimaginable to a people who had never seen a road or fence.

Within this context lies the inspiration of these new paintings for the show. Smith will have between six to nine works in Cowboys & Indians, including Bison Leather and Skull Pit.

As he explains, “There is great freedom in making pictures that are not bound by reality or a planned progression in a design. Starting with a simple idea I work out a simple composition around it, which will revolve the colors and shapes that are fluid and unplanned. My attempt, first and foremost, is to create pictures, and imagery that are unlike anything that has come before. I will be the first to admit that some attempts at this are more successful than others.”

Nostalgia filled cowboys grace the recent canvases of Arizona based artist Maggiori. He will have around 10 new paintings for the show ranging in size from 16×20 inches to 30 by 40 inches.

“I love to paint and dream about the old times,” explains Maggiori. “Cowboys always represented, for me, a time when America was still a promise land…a huge dream for whoever wanted it, before corporations and plastic.”

He continues, “I am trying to paint pieces that will tell a story itself and bring to the viewer certain nostalgia, a moment to remember what it felt to be riding a horse on a wide-open range. I am so fascinated by the era 1860 to 1910 in Europe and in America. Those were some golden ages.”

Maggiori is also fascinated with older leather, fabric and textures, and incorporates them into his works. “That’s why I am not painting modern cowboys…they are usually wearing too much bling.” Jokes Maggiori.

Also in the new batch of paintings will be nocturne paintings. He says, “I think night and moonshine bring such a mysterious and enigmatic element to my paintings. It is really hard to paint because sometimes you can get lost in the darkness of the colors…but the reward of the rendering is magic.”