Tim Solliday’s paintings present a poetic vision of an earlier time

By Gussie Fauntleroy

This story was featured in the July 2017 issue of Southwest Art magazine.

The first time Tim Solliday walked into the Los Angeles home and studio of the artist who would become his most important teacher, it felt like stepping into a movie from the 1920s. The ramshackle Spanish-style house was filled with antique furniture and décor: Oriental carpets covered the floors, while paintings, sculptures, stacks of prints, and other art objects were scattered about.

Looking back, Solliday finds it appropriate that Theodore Lukits (1897-1992) seemed to belong to an earlier era. Through the Lukits Academy of Fine Arts, the Romanian-American painter was offering something that—in the mid-1970s, when Solliday studied with him—had long gone out of style in American art education: academic instruction in the atelier manner, taking students slowly through the foundations of drawing and painting, beginning with only black and white.

At a time when representational painting was overshadowed by abstract and conceptual art, Lukits and his school filled a void. “Almost nobody knew who John Singer Sargent was when I was a kid,” Solliday laments. The atelier approach was a perfect fit for someone who left a Long Beach-area college because the art instructors had nothing but ridicule for Norman Rockwell and the other illustrators he admired; someone who since childhood had been mesmerized by great painting but was told it would not be possible to make a living that way. “I thought traditional art was dead on the vine, but I still believed I would do it,” Solliday says. “I always thought there was room for everything in art.”

In fact, he was right. Not only did collectors open their arms again to landscape, still-life, and figurative art, but Solliday—who paid for his art instruction by working as an apprentice billboard painter in Southern California—was right about his own ability to forge a successful career in representational fine art. His widely collected work is now in the permanent collections of the Briscoe Western Art Museum and the National Museum of Wildlife Art and has been exhibited at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, the Autry Museum, and the Carnegie Museum of Art, as well as other museums and galleries.

Solliday’s early conception of his artistic future leaned toward the illustration field. His father was a technical illustrator for Douglas Aircraft Company, a job that took the family from Solliday’s birth state of Iowa to the Palos Verdes Peninsula in Southern California, where as a young teen he had a horse. Although he had no interest in technical illustration, he was inspired by his father’s artistic ability and obsessed with drawing. Meanwhile, western movies of the 1950s and early ’60s left a lasting impression, offering a glimpse of how effectively visual qualities could stir the emotions and convey particular moods.

When Solliday’s college foray into art turned into disappointment, billboards became his training ground. In those days the work was often done in hangar-sized studios where mechanical scaffolding positioned a painter where he needed to be on the 14-by-48-foot image. Solliday learned to handle paint. He adopted disciplined work habits. He became adept at depicting texture—everything from a beer can to a horse to a girl on the beach. And it was through his fellow billboard painters that he learned of Lukits. In the 1940s and ’50s the billboard company routinely sent painters to Lukits to refine their skills. That was no longer happening by Solliday’s time, but individual billboard painters would go to Lukits on their own after work, often inviting fellow painters in whom they noticed an unusually high level of interest and talent.

So it was that Solliday found himself at Lukits’ home and studio, feeling as if he had stumbled onto a Hollywood movie set. That first night he was the last of the students to leave. Finally glimpsing the possibility of art instruction that matched his goals, he felt a kindred spirit in the older artist, then in his 80s, and the two talked until well after midnight. “I thought, okay, he’s a source of knowledge for me,” Solliday recalls. For five years he went to Lukits’ studio two or three nights a week after work. The intensive instruction began with learning to draw not from live models but from plaster casts or marble sculptures of the human form. From this came an essential understanding of using values of light and dark to produce a sense of three-dimensional form. For Solliday it was a revolutionary way of seeing and of rendering what he saw. “I thought, wow, what a difference from trying to draw from out of your head.”

Eventually, color came into the mix. Lukits would set up still-life arrangements for the students, presenting increasingly complex color problems to work out in paint. He used special lighting to simulate various conditions of outdoor light: intense yellow overhead for midday, blue for moonlight, a slanted angle of warm light for sunset, or a veil to mimic fog. “He was very honest,” Solliday says of his teacher. “He told us we’d never learn true color until we got outdoors, but he also knew it’s very difficult to paint outdoors, so we had a head start.” Soon the young artist could look again at the work of artists he admired and see what made them great. “It was thrilling,” he says.

Among the earlier painters who made a lasting impression on Solliday were illustrator Dean Cornwell (1892-1960) and Cornwell’s mentor, Anglo-Welsh artist Sir Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956). By studying Brangwyn’s paintings and drawings, Solliday began to understand that an arresting composition starts with massive shapes and the juxtaposition of forms. Brangwyn, and Monet before him, also opened Solliday’s eyes to the use of broken color, which lets the viewer’s eye mix colors that are adjacent on the canvas, having been applied as separate brush strokes. “It’s all about colors bouncing off other colors, or the illusion of brightness by adding gray around the strong colors,” Solliday says. “I’m known as a colorist, but if you study my work in person, you’ll see a great deal of gray.”

Solliday especially admires the use of gray to influence color in the work of western painter Frank Tenney Johnson (1874-1939). As it turns out, Solliday worked for a time in the Alhambra, CA, studio that once was Johnson’s. He’s also had use of the former studio of William Merritt Chase (1849-1916). These days the 65-year-old artist stands at his easel in the light-filled space on the top floor of the historic First Baptist Church—one of Pasadena’s largest, built in 1926. With arched stained-glass windows and a high ceiling, the studio has a touch of the medieval but with fresh white walls and state-of-the-art lighting that Solliday installed when he leased the space two years ago. It’s worth all the steps he climbs each day to reach it, he says.

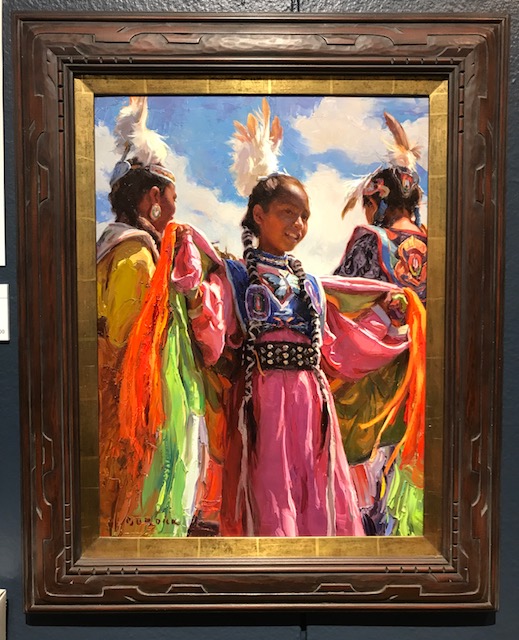

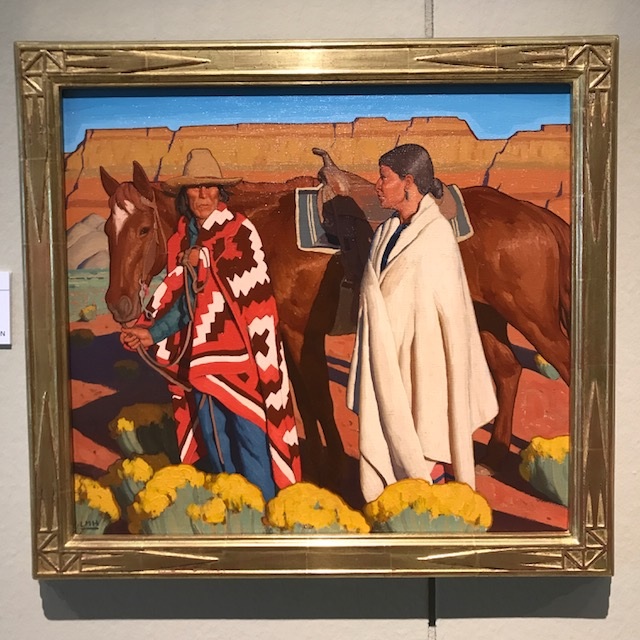

For many years Solliday was known as a landscape painter, capturing California’s natural beauty, especially through his plein-air work. He continues to use the landscape as the setting for his imagery, but now his focus is on the Native Americans, mountain men, and others who carried out their lives on the land. It’s a full-circle swing back to his boyhood fascination with the Old West—minus the confrontation—with special inspiration from the work of the Taos Society of Artists. When Native people and European-Americans interact in Solliday’s paintings, as they do in FRONTIER COMMERCE, it is in quiet encounters reflecting a feeling of mutual respect. The painting, as with much of his work, gave the artist an opportunity to combine intricate details, like beadwork on clothing, within the almost stage-set context of beautifully balanced color and solid, muscular shapes.

Similarly, COURTSHIP places a young Indian couple in a forest of dappled sun and shade as a horse grazes close by. “It’s about love blooming out of the peacefulness,” Solliday says. Both paintings are part of this year’s Prix de West Invitational show at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, on view through August 6. The two paintings reflect the artist’s shift not only in subject matter but also painting style. In both areas, Solliday has moved to a less literal, more imaginative approach. “It’s all based on classical principles of composition, light, and drawing,” he says, “but I had to come to a place that’s a little more free.”

What this means when he starts a new painting is sitting down with paper and scribbling abstract lines and shapes until they begin to suggest compelling forms, and a painting idea emerges from there. Then he turns to his trove of plein-air sketches, his collection of books and artifacts, and a well of artistic knowledge to flesh it out. More important than a literal interpretation is a feeling and mood that “moves the soul,” he believes. Like the best filmmakers who use camera angles, filters, and composition to produce a visually memorable scene, Solliday understands the powerful visceral impact of thoughtfully rendered color and form. “Every time I saw a poetic scene in a movie, especially westerns, it went into my mind,” he says. “And now it’s coming out.”